The Church of Santa Maria Assunta at Pernosano

The seemingly normal modern day Church of Santa Maria Assunta at Pernosano is, in fact, anything but. The true nature of the church’s distant past came to light some thirty odd years ago when an earthquake in 1980 revealed the ancient columns of a Medieval church that had stood patiently in wait beneath the modern church’s foundations for almost a millennium.

A brief history of the church

The first document that we have attesting to the existence of the medieval church dates to 1195 and credits Landolfus I, prince of Capua and Benevento from 910-943, with its creation. However, by 1591 there is evidence that the bishop was trying to persuade the local population to abandon the church because it existed in a plain particularly prone to flooding (this is distinctly evident in the stratigraphic sequence of the site, which points to frequent episodes of sediment build-up). In the early 17th century it is known that the town fell victim to several bouts of plague and subsequently, in 1654, the community at long allowed for the modern church to be built above the old one with its predecessor converted into a series of crypts used well into the 19th century. While plague does not manifest itself skeletally owing to its fast acting nature, archaeological evidence — such as horizons of lime ash used to sanitise certain layers of the crypt —provide support for documentation mentioning its occurrence. In the 1800s, several centuries following these devastating outbreaks of plague, destruction and looting befell the town of Pago del Vallo di Lauro, first caused by the influx of French troops and later by that of the Bourbon army.

Tour of the Medieval church

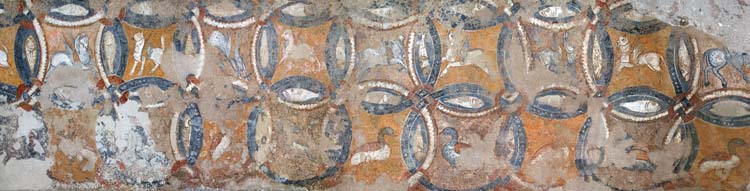

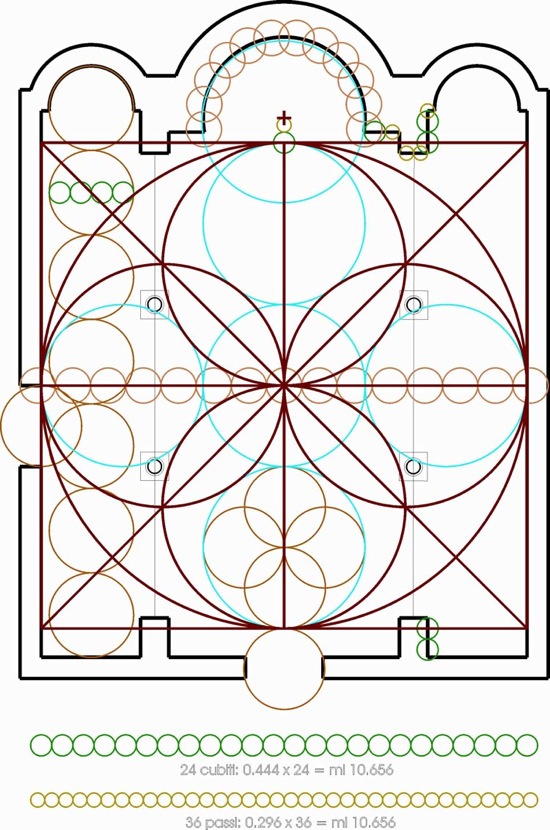

One fresco in particular has provided substantial fodder for debate among art historians. Located in the right apse, it once featured depictions of various creatures across divided across three registers, although now only the bottom two remain visible. The bottom register shows animals that exist in nature, such as ducks; these are brightly coloured, the green of which aids in the conveyance of an especially naturalistic representation. The level above is composed of mythological animals such as griffins, with an impressive palette including a vibrant golden-yellow. The top level is now sadly missing. The three levels together are believed to have represented a kind of ‘divine order’ of beings ascending from earth to heaven. Each of these individual images is surrounded by a decorative circular motif, the original stencilled lines of which are still visible through the fresco. Between the circles, small fish can be discerned, these being a well-known symbol of Christ. As a whole, the motifs are rather unusual and only two points of reference have been identified.

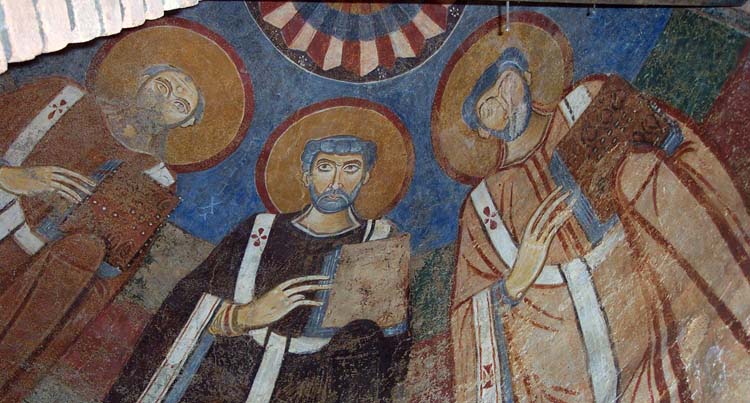

In the central apse, the three saints of Nola are represented. These are the first bishop, St. Felix Martyr, St. Maximus, the second bishop of Nola, and St. Paulinus, notable as an early Christian poet and the founder of the Palaeo-Christian basilica at Cimitile. The figures are much larger than the animals in the right hand apse, and seem to loom over the viewer. The colours used here are also remarkable for their vividness.

Towards the front of the old church is a hole, which is all that remains of an ancient font. It is here that immersion as a form of baptism used to take place. The seat of the bishop would have been in the large central apse that is still mostly unexcavated, looking down onto the immersion pool. It is known that in early Christianity the ritual of baptism was far more exclusive than it is today. Baptisms could only take place at Easter, and as only Christians were allowed inside a church, your baptism would be the first time you entered. The secretive nature of such ceremonies, which required the baptised person to be fully immersed in the water, was a throwback to the earliest days of Christianity when it was a cult on the fringe – albeit with some very influential members. This exclusivity started to change from the eleventh century onwards. As population growth accelerated throughout the eleventh and twelfth centuries, increasing numbers needed to be baptised at an increasingly faster rate. This led to the adoption of the stone font more familiar to church-goers today, and only a few splashes of water were required.

Innovative deep excavation strategies were employed to better understand the nature and extent of the medieval church here under study. In most instances of deep excavation, large and terraced trenches are used to minimise the danger of collapse. What makes this site especially challenging is that it has another church built on top of it, presenting a potentially hazard due to the weight. As the old church below was excavated, the ground bolstering the structure was effectively being removed and an empty space created into which the upper, more recent church could collapse. Needless to say, excavation progressed slowly. After every fifty centimetres of excavation, archaeologists had to stop in order to reinforce the structure around them with scaffolding to prevent what very likely would have been a fatal collapse. The nave of the church above is twelve metres high, so the structure is extremely heavy. That the structure exists largely underground and has been occasionally subject to earthquakes was another reason for caution. As work progressed, it became necessary to further support the lower church, and modern masonry combined with some high quality restorative work has made it safe to visit.

Today, the upper church functions dually as both a museum and as a conference centre. The first century inscription is displayed alongside high quality models of both the upper and lower churches. Various finds from the excavation are on display, primarily ceramics. The disinterred human remains are housed in a large annexed storage room. This collection of skeletal material consists of a minimum of about 60 individuals and preservation appears to vary from good to excellent.